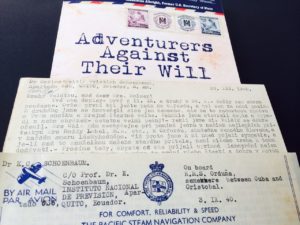

Adventurers Against Their Will:

A Lesson on the Difficulties Leaving Nazi-Occupied Czechoslovakia

For questions about these lesson plans, contact Author Joanie Holzer Schirm, joanie@joanieschirm.com. Primary source documents used in this lesson plan are a part of the Holzer Collection. www.joanieschirm.com

Rationale for the lesson: When studying the Holocaust, the question, “Why didn’t the Jews just leave?” often arises. Students today tend to believe it is easy to move from one country to another, often not considering the many obstacles, such as language barriers, availability of jobs, finding a new home, and the possibility of leaving family and/or friends behind. In addition, there are legal issues in attempting to move to a new country. This activity shows students that it wasn’t a simple decision and that even when some did decide to leave, laws made it impossible to do so.

Rationale for the lesson: When studying the Holocaust, the question, “Why didn’t the Jews just leave?” often arises. Students today tend to believe it is easy to move from one country to another, often not considering the many obstacles, such as language barriers, availability of jobs, finding a new home, and the possibility of leaving family and/or friends behind. In addition, there are legal issues in attempting to move to a new country. This activity shows students that it wasn’t a simple decision and that even when some did decide to leave, laws made it impossible to do so.

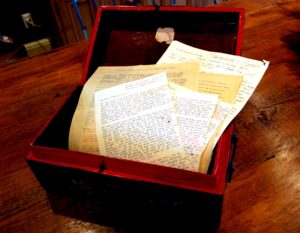

If you are utilizing the entire book, this activity can be used any time after the 1940 letters begin. This assignment is to give the students a sense of the letters and what is happening to those trying to leave Nazi-occupied Bohemia and Moravia (Czech lands from prior Czechoslovakia).

If you are only using selected letters, we have several here that can be put together as a packet. Students can be assigned to groups, and each group can read one letter. In their discussions, have each group consider the following:

- What is the focus of the letter?

- What options do the letter writers have for leaving?

- What questions do the writers have about leaving?

- Do they have any regrets? If so, discuss them.

- What is the tone of the letter?

After discussing amongst themselves, have each group share their findings. Then distribute the handout (found here). Point out the requirements needed just to leave Germany! (Czechoslovakia had the same laws). Next, read the requirements to get a visa to the US; again, similar laws applied in most countries. Ask students to apply specific requirements to the letters they just read.

Prior to reading the letters, please give the context of the book, Adventurers Against Their Will, explaining that the letters are actual letters written by and received by Dr. Valdik Holzer from his friends, all of whom are from Czechoslovakia. You might want to use a map from the 1930s to show the area and the places each of the friends fled to.

Letter 1:

March 6, 1939

Letter from Bala, in Prague to Carl Ballenberger, in Cleveland, Ohio

**Bala’s real name was Karel Ballenberger. He was a politically active lawyer who left Prague for London in 1939, leaving behind his wife and 2 children, who all later were murdered in Auschwitz. Bala was injured in WWII in France, but survived the war and remarried.

Dear Sir,

It is to Mrs. Stastna-Eksteinova that I am indebted for your address. I am a son of Leopold and Hermina Ballenberger from Praha-Blanik/Smichov, who was a cousin of yours. This relationship authorizes me to ask you a great kindness, to grant me an affidavit of support and enable me thus to go with my wife and family to immigrate to USA.

I hope you are informed about the political and economic situation of the actual Republic of Czecho-Slovakia. The growing anti-Jewish trend and the general economic circumstances seem not to allow in the next future any Jews to work and live in Central Europe.

I am 30 yers old; my wife Milena, whose maiden name was Langer, is the daughter of Dr. Leopold Langer, is 26 years old. We have two children, Alena, who is 3 years old and John, who is only 1 year old. I am enclosing their photographs.

At present I am running a barristers’ office in Prague, but I am afraid I shall not be allowed to act as a barrister any longer, should anti-Jewish measures come into force, and shall, therefore, have to try my chances somewhere else.

I studied law at the Czech University in Prague, and Doctor of Laws and have had good experiences in commerce. Besides Czech, I speak rather well, English, French, German and Spanish. My wife speaks the same languages and possesses commercial experience too. She is a chartered nurse. The personal particulars of my whole family are enclosed.

I assure you, Dear Mr. Ballenberger, that, should you make up your mind and send [unreadable-copy is on the fold of the letter] any member of our family affidavits, that we are prepared to do anything to earn our living. I have no other relatives in the USA and am sending you this depressing letter with my greatest reluctance, forced only by the present strained circumstances.

I hope you will kindly do what is in your power and thank you together with my wife from all my heart for whatever you will be kind enough to do for us.

Yours very respectfully,

[signed] Karel Ballenberger

1 photo, 1 enclosure

Dr. Karel Ballenberger, Prague XVIII, Vorechovka, Slunna 4.

Czecho-Slovakia

Letter 2:

November 15, 1939

Letter from Karel in Oxford

*Karel Schoenbaum worked as a lawyer and escaped to London with his wife, Katka. He earned his Ph.D at Oxford and was able to get to the U.S. in 1941, where he changed his last name to Sheldon. His daughter, Carol, was instrumental in helping the author of Adventurers Against Their Will trace the paths of the adventurers.

. . . I got a free place at Oxford University where I am preparing for my Ph.D. studies. I am at the New College, which is not new but very old and very prestigious. Everybody is really nice and pleasant and apparently they like us, especially my wife, Katerina. That won’t surprise you!There are approximately thirty Czechoslovakians here, and we have organized a small discussion group of which I was chosen the leader, and we do what we can. From home we have little news, nothing direct, of course.

But that which we know is in no way reassuring. About my parents, I only know that they had to leave the villa in Bubenec and they are either with the Nejedlys [Andula’s relatives] in Mezimosti or in our little house in Jevany [a village east of Prague]. Uncle Karel, whom I like so much, was arrested. My uncle Emil got out and will be a government consultant in Ecuador. My old friend Emil Sobicka was apparently dragged to a concentration camp; Zdenek Thon also taken, if he is alive. The Matuska family is relatively well off. The Slovaks are better off than those in the so-called Protectorate.

Letter 3:

December 7, 1939

Letter from Valdik, in Shanghai to Rudla, in Villa des Cytises, France

*Valdik is the father of the author of Adventurers Against Their Will. He studied medicine at Charles University, Prague, and escaped to China when the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939. He married Ruth in China and they later settled in the US. Thanks to Valdik keeping all the letters, we have the book and these stories.

. . . I am waiting for you to write to me some interesting things that the people in the Protectorate can’t write. All the correspondence that arrives is inspected, and mother writes some things that I am afraid for her that she’ll get arrested and locked up.

. . . I am waiting for you to write to me some interesting things that the people in the Protectorate can’t write. All the correspondence that arrives is inspected, and mother writes some things that I am afraid for her that she’ll get arrested and locked up.

Otherwise, lately they did not write much. Their letters are full of optimism, which I do not believe. My father is working up until now. They write that they have enough food; who wants to believe that? I am concerned about them, especially after the last uprising; the news is that they are evacuating those who are not “dependable” to Poland.

I am not badly off; I have my own surgical practice, and I earn enough pocket money for a cup of tea for breakfast. In time, it will get better. I am waiting, because I have applied for another position and perhaps will get it.

I had malaria and paratyphoid, and I am not yet well. But please do not mention this when you write home. Here in Shanghai it is not at all pleasant; about 20,000 immigrants are here, mostly without any money. Out of them, 18,000 are living in the ghetto. You cannot imagine what it is like in the ghetto for escapees in the Orient. Most of them have died from different infections.

Altogether 500 doctors came here, of whom 300 have opened their own offices. Shanghai has its own population of five million. It is a small nest because there are only 80,000 white people, out of whom 20,000 are Russian émigrés and the rest one meets in two months. The Chinese people live separately, and it is not suggested to be friendly with them.

Letter 4:

Rudla’s response to Valdik

*Rudla is Valdik’s first cousin and a successful banker. He and his wife Erna fled Czechoslovakia first to Italy and later to France, where he left his family to serve with the Czech Army in Exile in Britain, where he remained the rest of his life.

. . . It is different with me. We had to register voluntarily and I have the impression that I will only stay with the family at most until the end of January. I like it here very much; the people are quite different. I wish I could stay here in peace until the end of my life. But I have no employment as I cannot get a work permit, and I live in a small place where there is no prospect for work or some sort of beginning. I am trying to do business with stamps, and I hope that I will earn a franc or two.

I am not at all sure how long I will be able to stay here with my family. But at the present I am not unduly worried, because I have reserves of capital for our maintenance. But it is not pleasant to sit around without anything to do, not knowing what will happen next. We shall have to hope that the western states will destroy the regime so that millions of people can feel free. . . I am thinking of moving to the U.S.A. next year, but of course, only if it will be possible. At the moment we are all learning to speak French, we are making progress—especially Tomas, who attends French nursery school.

Letter 5:

January 11, 1940

Letter from Franta, in Bechyne (in the Southern Bohemian region):

*Franta (Frantisek Schoenbaum) was Valdik’s best friend. Married to a non-Jewish woman, he remained in occupied territory until the final months of the war, when he was imprisoned in Terezin. His wife, Andula, arranged to hide their son, Honza, in the countryside. They all survived the war, but the couple divorced. Franta remained in Prague.

. . . We are all really happy that you are doing well and mainly that we can learn something about you, as the others.. . are missing, completely. This place reminds me of an island where ships never dock. I am sorry that Franta and [our son] Honza cannot go outside but I can’t do anything about it, and from selfish reasons I am happy that we are all together.

Yesterday, Milena Balova [Ballenberger] and Viktor Schuch were here, so we remembered you vividly. Will we ever see each other again? Probably not. Valda, I am ceasing to believe it. Do you have a nice girlfriend there? Friends? We are left with two in total.. .

Do you remember how many people were constantly around us? But it doesn’t really matter; we have our little Honza and aren’t in Prague and all that.

Write a lot, Valda, so we get some pleasure and keep us in your kind grace and in mind.

Letter 6:

March 2, 1940

Letter from Rudla to Valdik

. . . As far as U.S.A. is concerned. . . the visas they are issuing now are for people who registered at the beginning of May. Accordingly, it could take about two years before we are called. But one never knows. Sometimes one thinks that things are bad at the time and it may be better later. I think it would be nice for us if we could get into the U.S.A. Of course, I have different reasons than you.

Only by a miracle am I still with my family. But I don’t know for how long. I am thinking that through some miracle of fate somewhere we shall stay together and that I will not be called up for the army. I don’t know what the explanation is. I am not pushing anything., You know me as a modest person.

. . . Really I wish I could live here in peace. You would see what it means for people to live in France. I love this nation and I am sorry that the nation next door is inciting it into war. I am sure that if I knew the language, I could earn a living here. I seem to be making progress, but Tommy is doing much better. Tommy talks like and old Frenchman. I wish I could speak half as well as he does. He does not feel that he is an immigrant. He likes everything here.

The way things are, the war will not end soon., It gives me more than minor problems thinking about the future. But we must live for the present. Who knows what will happen. We are constantly fighting with our nerves. It is not easy to keep them at rest.

Letter 7:

March 31, 1940

Letter from Karel from London:

Letter from Karel from London:

. . . Now the question is, though, whether those scums will let them out. I am somewhat afraid, according to the last news, that it will not happen. About the conditions at home I have very precise and regular news, also thanks to listening to broadcasts from Prague. It is not cheerful, believe me, Vladik. Those of us who luckily got out early cannot even imagine. I remember how we were hunting for those documents and tickets together; it has just been a year! How the time flies.

The letter that you mention, the one that was supposed to be passed on to me by Bala, I never received. But we aren’t in touch at all now. He is the only person with whom I had to, here in emigration, part in bad blood. He did not behave properly to Katka or me, and, mainly, he couldn’t take the fact that I got this position here in Oxford.

I can understand his situation, with Milena and the children being in Prague, and I continue to have a lot of sympathy for him, particularly vis-à-vis this aspect. Though he bears a lot of guilt that Milena did not get here, he kept hesitating and fearing that life in exile would not be sufficiently comfortable, etc.

Above all, he doesn’t allow himself to go without much. He is a person constantly driven by inner restlessness, incapable of staying in one place and without company for one second. In reality, I really pity him—after all, we were friends for a long time. He acted in a strange way, however, so what. Please send your letters directly then.

Letter 8:

August 2, 1940

Letter from Valdik (in Ping Ting Hsien) to Hana

. . . Yesterday I got a letter from your dear parents, which I am enclosing. Like to you, I wrote to them through addresses of friends in neutral countries. How they can also serve as intermediaries you can see form the enclosure. I wrote to both friends simultaneously but so far I have not received any answers. I believe it will be best for now if you send some letters to me and I will mediate the connection for you. It will take a bit longer, but they will be calmer at home if they get something at least. Anyway, I think you don’t have to feel completely abandoned as you have a number of relatives in England.. .

My parents were expelled from their apartment since the building was “Aryanized.” They moved to Slezska Street on July 1. They didn’t give me the address for whatever reason; every little stupidity now worries one. It seems they get together with your parents very often and so at least both don’t miss us so. This month I got two letters from Sebirov [township]. It seems all is well there.

Pavel Kraus has not called on me for about three months now. I, therefore, don’t know how and what he is doing.

Did you ever look up my friends in London whose addresses I sent you?

Letter 9:

February 1, 1942

Letter from Hana (in Southport) to Valdik:

*Hana Winternitz is another of Valdik’s first cousins. She escaped to Holland and then to Great Britain in 1939. She worked as a domestic helper throughout the war and then received a scholarship to business school. She later married and had 2 daughters, and remained in the UK.

. . . Before America entered the war, Uncle Spitzer got a letter form his parents in which they asked him to get them a Cuban visa and boat passage (which they later rescinded).

He did what he could to get that visa, but America’s entry into the war ruined it all. It must have been a huge disappointment for them since they had been able to get all the complicated permits and then it all fell through.

It made me very upset in the beginning. However, it is partially their fault, they had an opportunity to go to Palestine when the Polaks went. Partially it is my fault as well. After the fall of France, I should have been more energetic and left. Anywhere would have been fine. My parents would have followed me there. Now they can’t.

Talking about it is easy; doing it is harder. What happened, it’s done now, and I will not have any news from them until the end of the war; I am not the only one, unfortunately.

©JoanieHolzerSchirm